After The Brand Flip

Several years ago, I came across Marty Neumeier’s book The Brand Flip.

The book argues that before, companies built brands that attracted customers who then bought into the brand and products. Today, customers build brands for companies. He called this shift The Brand Flip. It’s a simple and elegant framework that emphasizes the need for branding managers to shift focus from the product to the customer and from experiences and materiality to meaning.

Consumers gained real-time access to others’ voices via mobile devices. The launch of the iPhone impacted mass smartphone adoption. Prior to this, consumer voices like reviews were accessible, but accessing them at the point of purchase even in physical stores changed the power dynamics between brands and consumers. The transparency gave more authority to consumers.

Neumeier says, “Your brand isn’t what you say it is. It’s what they say it is.”

The book was written in 2015. While the shift in consumer power and Neumeier’s points remain true and relevant in 2025, a decade is a long time and the market and consumer mindsets have evolved.

Since 2015, the importance of products and the surrounding experience in brand-building has risen considerably. They now play a more crucial role than a decade ago.

What changed since 2015?

2015 - 2025: What changed?

Four key factors changed in the power dynamics between brands and consumers, or institutions and individuals from 2015 to 2025.

1. Short-form mobile video

In 2015, TikTok hadn’t even launched yet. This statement alone speaks volumes.

It was 2018 when ByteDance acquired Musical.ly and merged it with Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok. This accelerated mobile video adoption and transformed information access. Out of over 170 million US TikTok users and one in three adults, 52% get their news from TikTok.

Now, mobile devices, fast networks, and quality cameras let users create and share videos anytime, anywhere, and just about anything.

This didn’t exist in 2015.

2. Individuals as brands

The rise of mobile devices gave people the power to access information. The ability to create and share videos gave them reach, influence, and power that only brands and institutions had before.

The terms “influencers” and “creators” are relatively new. “Influencer” was added to the Oxford Dictionary in 2019, which is surprisingly recent. The term “creator economy” existed, but SignalFire’s Creator Economy Report in late 2020 gave it greater visibility.

Over 95% of the top 100 most followed accounts on Instagram and TikTok are individuals, not brands or institutions.

People are more interested in other people, not brands.

In the last decade, platforms like TikTok and YouTube, and formats like podcasts gave individual creators more presence, authority, and influence than in 2015.

Back then, CNN had more power and influence than the likes of Joe Rogan and Alex Cooper. The Republican presidential debate on September 16, 2015, had its best viewership, with 23.1 million viewers. This was difficult for individuals to achieve back then.

In 2025, Joe Rogan’s podcast with Donald Trump garnered 26 million YouTube views in 24 hours. His reach (11 million downloads per podcast episode excluding YouTube) is now bigger than CNN, MSNBC, and Fox combined (700,000, 1.7 million, and 2.1 million respectively). This was unfathomable in 2015.

People trust individuals more than they trust brands and institutions. This has always been the case.

Social videos and podcasts put this into overdrive.

3. Product-as-Content

The nature of online content has also changed.

For instance, in 2015, music videos, comedy/prank videos, and TV show clips dominated YouTube. By 2025, content like product reviews replaced them, with related channels growing in popularity. The biggest YouTube creators focus on this because they attract views.

“Product-as-content” wasn’t familiar back then. Its origin is unclear, but it started appearing in 2015. A Fashion Institute of Technology white paper mentions “The concept of product as content,” and Mitch Joel, President of Mirum, predicted that 2016 would be “the year when the worlds of product-as-content and content-as-product collide.”

Human Made, a Japanese streetwear brand founded by NIGO and Pharrell Williams in 2010, remained modest for a decade. Around 2021, it started a weekly newsletter highlighting its product collection. This project-as-content strategy resonated with its fanbase, leading to rising sales. In three years, revenue quadrupled. It didn’t need a viral campaign to raise awareness and demand for its products. It acted like a publisher and published its products as content regularly. The fans craved more, the fanbase grew, and so did its business.

4. Heightened consumer expectations

In the last decade, consumer expectations about products and the purchase process rose as consumers gained more power.

Amazon Prime has spoiled us and made most online businesses resent it. If they sell on their own, they are forced to offer free shipping and returns. If they sell on Amazon, the cost eats into their profits.

If we didn’t like what we bought, we could just return it with little consequence and even without leaving our homes. This puts pressure on companies to ensure their products deliver on promise and value.

This isn’t limited to e-commerce. Positive experiences in one sector inform expectations across others. Consumers expect the same ease in retail or healthcare across all brand interactions.

The Flywheel of Trust

These four factors—short-form video, people as brands, product-as-content, and heightened consumer expectations—shifted the power dynamic between brands and consumers, elevating the importance of products in brand-building.

In his Brand Flip model, Marty Neumeier argues:

Company creates Customers

Customers build Brand

Brand sustains Company

This thinking is based on two of Peter Drucker’s most famous quotes: “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer” and “Business has only two functions — marketing and innovation.” Both must play a role in creating and keeping a customer.

Drucker and Neumeier are making general statements without including products. That might have been fine in and before 2015.

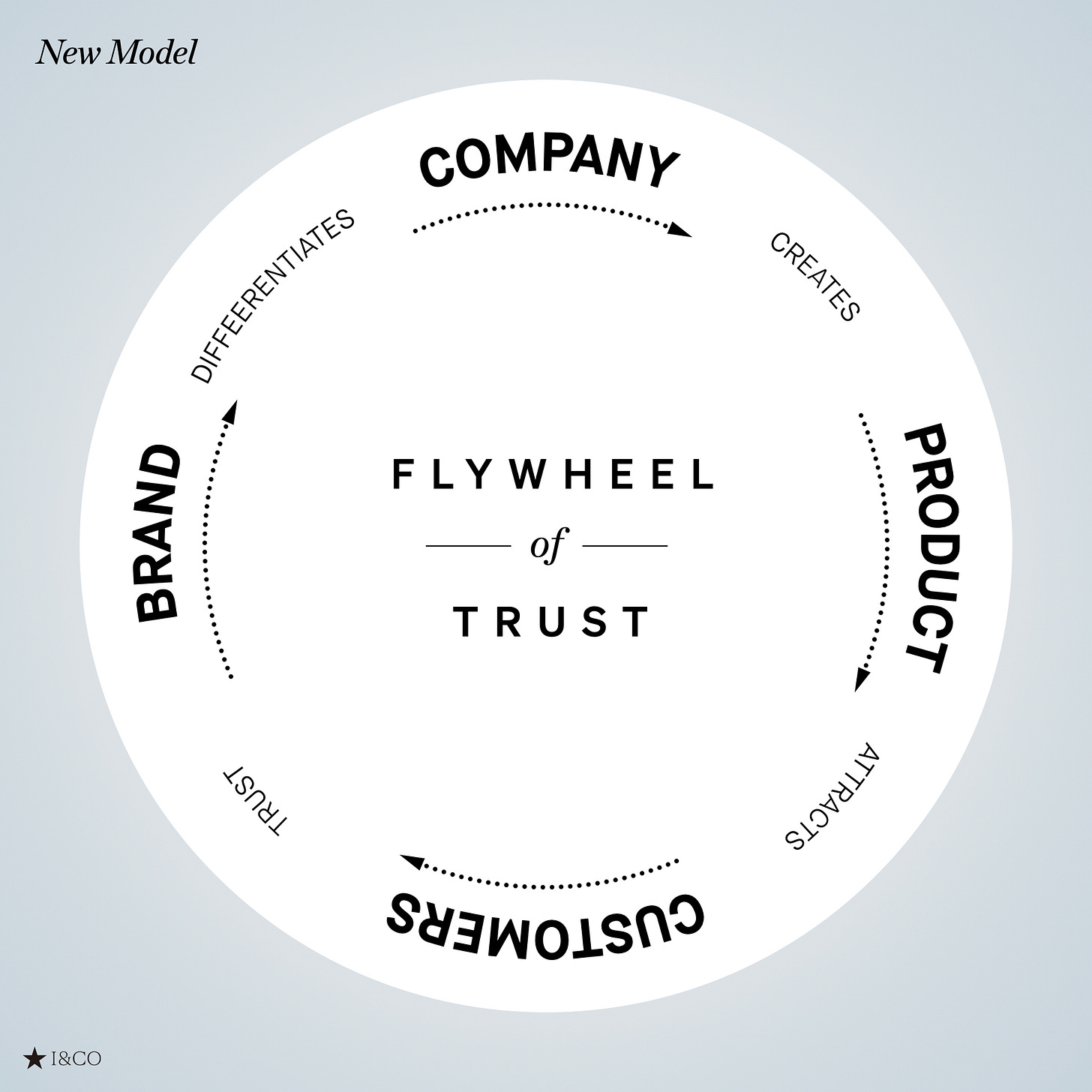

At the foundation of a new framework I call the Flywheel of Trust lies the product itself. It is now the main driver in attracting customers.

In the last decade, we’ve seen this phenomenon increase.

Stanley’s Quencher, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Uniqlo’s Round Mini Shoulder Bag, and lesser-known cases like Human Made’s weekly product drops.

All these brands gained traction without heavy marketing. Rather, their products became the best marketing.

The product and its experience must deliver trust, building the brand, which then differentiates the company that created it in the first place.

The Flywheel of Trust goes on.

Company creates Product

Product attracts Customers

Customers trust Brand

Brand differentiates Company

In my next essay, I will explore cases of the Flywheel of Trust in action and how to use it for your brand.

Great piece. I've always believed brands are built in the trenches of consumer behavior, not boardrooms. The Brand Flip was a wake-up call, but what fascinates me now is how we've moved beyond flipping—it's more like fracturing.

Consumers don’t just shape brands; they co-own them in real time. They remix them, hijack narratives, and force companies into a constant state of adaptation. If brands don’t embrace this dynamic shift, they risk becoming relics in their own industry.

Nice insights, Reí. In your follow up it would be great to hear how you see this applying to B2B as well. I agree with your points and while it is easier to see these trends taking shape in B2C, I think most underestimate this has also already happened in B2B as well!