POV > AI

Why a point of view (POV) will be more important than AI

“Oh, clients have to pay,” says Pum Lefebure with a laugh.

Pum is an award-winning creative director with more than two decades of experience in design and advertising. When she says this, she is referring to a client project in which she utilized AI heavily to produce the work.

As the co-founder and chief creative officer of Design Army in Washington, DC, Pum oversees all creative coming through her agency's doors. Pum is a dear friend who, like me, is from Asia. We built our respective careers in parallel in different corners of the design and advertising industry as immigrants trying to make it in America.

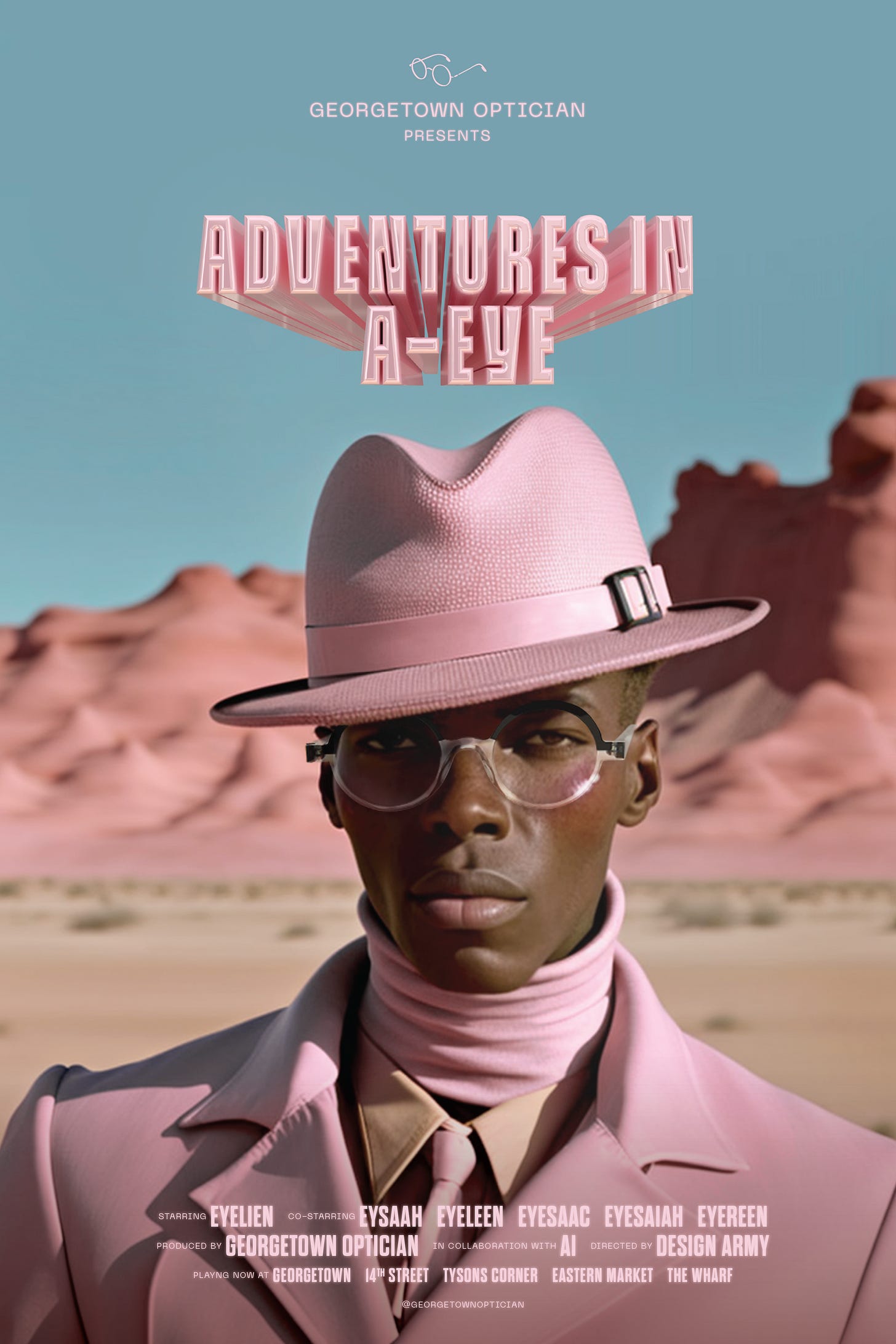

In 2023, she and her team launched “Adventures in A-Eye,” an advertising and branding campaign for one of her clients, Georgetown Optician. A campaign of this caliber, without AI, would have taken several months and cost $500,000 or more to produce, says Pum. Naturally, my question at this point in my conversation with her is this: How much did it cost?

“I can’t tell you.”

Fair enough. I expected as much. But I can make an educated guess.

Process

This project started with a phone call from the client, Pum says.

She had worked with Georgetown Optician before. “We are opening a new store and would like your help promoting it.” Typically, she would be given several months' notice for this type of ask. Four months to be exact, according to Pum. I concur, having worked on numerous campaigns of different sizes before.

For Pum and I, as creative directors, our instinct would be to gather a team that consists of a strategist, a project manager, a copywriter, and a designer or two, to start. This would be what we consider to be a minimum viable team. It would take at least several days to formulate a project plan, a proper brief with specific deliverables, and metrics for success, to name a few, to kick off a project.

From there, we would want to give several days to a week to the creative team to come up with ideas, and then a few more days for the creative director to push the team and refine them. What we present to the client would be initial ideas with some visualizations to help bring them to life. We see the client’s reaction, address their feedback, and go back to the client a week or so later. We might repeat one more round and by this point, about four or five weeks in, we want to have a clear, refined direction that is approved. We then can start preparing for production.

I’ll spare the rest but to break it down, the whole process would look like this:

Week 1: Call from client, prepare project plan & brief team

Week 2~3: Concept

Week 4: Present initial ideas to client

Week 5: Refine & present again

Week 6: Revise & finalize

Week 7~8: Prep production

Week 9~10: Shoot/production

Week 11~14: Post-production & client reviews

Week 15~16: Finalize, create variations & deliver

This is a 16-week or 4-month process, over-simplified for the purpose of this essay. It is not an unusual nor unreasonable timeline if a client wanted something that was professionally produced.

Or at least it would not have been, before AI.

Drawers in our brains

As middle-aged creatives like Pum and I (sorry, Pum, for calling you middle-aged!), we have many drawers inside our brains. The more experience we gain, the more drawers we build.

Tinker Hatfield, the legendary sneaker designer of Air Jordans and other numerous hits from Nike, said this: “Creativity is a function of the library in your head. When you sit down to create, it’s a culmination of everything you’ve done and experienced up to that point.”

What differentiates a creative director from a creative is that creative directors—good ones, that is—know instinctively which drawer to open and pull out an idea at a moment’s notice, and add a twist to the idea to make it appropriate to the given problem at hand.

Many of those ideas in the drawers are random and we just never had the right opportunity or client to present. Others are ideas that we did present but never saw the light of day for whatever reason. For instance, I’m working on bringing an idea to life right now that I presented to the client in 2018. The idea was well-liked and we spent about a month preparing the execution but it turned out to be too expensive. In 2024, AI could change that.

For ideas to be bought and brought to life, numerous factors need to align. Perhaps that’s a topic for another essay.

When getting the call from the client, Pum says, her client told her they only had four weeks instead of four months. This was tied to the opening of a new store so there wasn’t flexibility. As not to digress, let’s not ask why the client waited until the last minute to call Pum. To be fair, though, there are often reasons beyond their control that we might not understand.

At the time of the client's ask, Pum happened to be experimenting with Midjourney as a hobby to design an imaginary living room or fashion outfits for herself. This turned out to be a moment she could open one of the drawers of ideas and inspirations.

“I always had this idea of space tourism and people dressed in a stylish, retro-futuristic way.”

By this alone, it’s just an interesting visual. To make it relevant to the client, an eyewear brand, Pum did three things. Those three things came from Pum’s experience: story, craft, and speed.

Story

The first is how Pum was able to connect this loose visual idea to Georgetown Optician by creating a backstory.

“What if these people, all fashionably dressed, traveled to an imaginary planet, and this planet had a different climate with UV and dust that required the travelers to wear glasses to protect their eyes?”

This was the twist she added to the original idea from the drawer inside her brain. Without it, there would be no conceptual connection between the product, glasses, and the visual, space tourism. The cherry on top was to name this idea “Adventures in A-Eye,” where “A-Eye” is the imaginary planet.

Without a name, we don’t know what to call the idea or how to refer to it. In just a few words, this name creates a clear and memorable impression.

Craft

Second, craft. One of the most surprising yet most important steps that Pum tells me that she took was how she rendered glasses, the very product that the client sells. Having experimented with AI, she learned that AI was good at rendering imaginary things but not good at generating actual things precisely as they exist in the real world.

She resorted to using photos of the products and compositing them into AI-rendered figures. This might not sound like a big deal but I do believe that this was the make-or-break aspect of her work.

It’s one thing to realize the limitations of a tool. It’s another thing to know how to compensate for those limitations and decide what to do. That requires experience.

This insight reminded me of another conversation I had with Chef Yoshihiro Narisawa last year. A Michelin-star chef and voted #1 in Asia in the past, Chef Narisawa creates highly elaborate dishes combining traditional Japanese, French, Spanish, and Chinese cuisine methods with newer gastronomical techniques.

Although he has dozens of chefs working under him, it’s Chef Narisawa himself who comes up with the recipes. When I asked him how he manages to generate such complex recipes, he said that based on his experience, he’s able to imagine the taste of the dish he’s creating.

Speed

After the call from the client, it took only a week and a bit for Pum to go back and present the work. In the old, traditional way, it would have taken her and her team of designers at least a couple of weeks to come up with initial and unfinished work.

In this case, not only was she ready to present the idea in a week or so, but she was able to present work that was pretty much finished and almost ready to go.

“How many designers did you have on your team?” is my next question at this point in my conversation with her.

“It was just me,” Pum says with both confidence and a slight hint of guilt.

On this project, since she had only four weeks, here’s how it rolled out:

Week 1: Call from client & concept

Week 2: Present (almost) finished work

Week 3: Add team & expand work

Week 4: Finalize & deliver

On this project, Pum played the roles of strategist, writer, designer, director, cinematographer, wardrobe stylist, and quite possibly more. And she did so in a week.

In the second week, she did bring on additional designers to help her expand the work and make it a more holistic campaign. She also knew that another one of the limitations (at the time) of Midjourney was that it was not able to render type well at all. That is where she utilized additional resources.

Regardless, before AI, this just wouldn’t have been possible.

The math

My educated guess is that she would have needed at least a few people supporting her after the initial week of her 4-week process. Let’s assume the average cost of a creative contractor is $125/hour. I could imagine having two designers/animators full-time, and additional resources such as a project manager and a writer at half time to support.

For this lean, minimum viable team for a month, the cost could be somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000 for a month of work. But that’s pure cost for the agency.

Instead of $500,000 and four months, her client might have gotten something in four weeks and for less or slightly more than $100,000. In theory, that is.

In reality, however, things don’t align this neatly.

There are several factors at play here. For one, the relationship Pum had cultivated over the years and the trust she had earned. That is years in the making, and therefore, costly.

Second, the many drawers in her brain.

When Paula Scher, a legendary graphic designer, gave a sketch of a potential logo in a meeting for Citi, the client asked how a logo could be done in seconds. Scher replied: “It’s done in seconds and 34 years.”

In Pum’s case, it was done a week and 25 years, and with AI.

In addition, the cultural zeitgeist of the moment in time. If she were to repeat the same process now, the work probably would not be as interesting or relevant.

As a whole, the process Pum went through isn’t easily repeatable or replicable.

$500 or $500,000?

As we are talking about the price of creativity, she brings up another past campaign she worked on and one of her signature pieces for a ballet company in Hong Kong. A beautifully styled and wonderfully choreographed, it is a modern, Wes Anderson-esque take on a classical art form. It has 228,000 views on YouTube.

On the contrary, three behind-the-scenes clips she shot on her iPhone and uploaded to her agency TikTok account have a combined 11.8 million views.

That begs the question: which is better? Spend half a million dollars on an expensive shoot and months of work that gets 250k views vs. $500 and shot on an iPhone that garners millions of views?

In this case, the cheap and quick option would not have been possible without the expensive shoot on location. But the question is something many brands wonder about.

For most brands, the answer to this question is that one is not better than the other.

Of course, there is nuance and gradation and each brand needs to calibrate. However, if we are skimping on a budget for marketing and advertising activities, it’ll catch up with us and we’ll either not gain enough or end up paying the price in some other way.

It’ll be a mistake to make a decision purely on price.

The question

The real question for creatives is the following: Why should a client come to us and pay more?

If the answer is the former, we are in a commodity business. The harsh reality we face is that the price is and always will be a sticking point with clients. Technology, throughout history, consistently commoditized an aspect of any business and therefore forces the price down. It’s an inevitability we can’t run away from. For creative businesses, we just didn’t think it would happen so soon.

Are they coming because they want something cheap and quick? Or do they want our point of view and value it?

The answer may not be as black and white as we want it to be. There will be shades of both.

But without a POV, we may as well let AI take over.

You can listen to my conversation with Pum Lefebre here (Episodes 23, 24, 25):

Apple Podcast:

Spotify:

Thanks for reading. Please hit reply if you have comments, questions, and feedback. I’d love to hear from you.

do they care that the images could be used by other companies? or is there something that stops this from happening? from what i understand ai art has no copyright protection . so sure, the images look great but every eye-glass co in every town could use the images, right?